Like many of today’s modern technological conveniences, electronic security products typically require a year or more to get from the drawing board to the stock room.They are the result of countless hours of brainstorming, research, development, testing, production,marketing and support. How do manufacturers do it? Take a journey with a mythical product to find out.

Like many of today’s modern technological conveniences, electronic security products typically require a year or more to get from the drawing board to the stock room.They are the result of countless hours of brainstorming, research, development, testing, production,marketing and support. How do manufacturers do it? Take a journey with a mythical product to find out.

Every motion sensor, DVR, card reader, control panel or any one of thousands of other electronic security and fire/life-safety devices in existence today was once just an idea put forth by one of our industry’s manufacturers. Most installers and end users take these products for granted as useful devices to be sold and used. However, each of them undergoes a long, rigorous process of research, development, testing, production and marketing.

Most manufacturers would agree — particularly if you talk to their customers or marketing and sales folks — that the time and cost involved in bringing a new product to market is substantial. Larger suppliers often have a gauntlet an idea must run in order to ultimately become a product. Smaller companies, on the other hand, are often surprised by the ramifications of skipping such “unnecessary” steps. Yet, if you were a fly on the wall at their meetings, you would likely hear a common plea: “Can’t we do this any quicker?”

To shed some light on how this all works, we’ll take a product through the entire process. We’ll explore the elements that go into a product design, and the millions of dollars and years of work involved for even fairly simple technology products.

To accomplish our task, we’ll create a fictional product. Since DVRs are popular now, incorporate hardware and software in their design, and are going through rapid innovation, we’ll go with one of them. Our manufacturing company will be a fictional but established player, with the infrastructure to design, build, distribute and support their products. Finally, we’ll stick to available technology — no holograms, nanotechnology, smoke, mirrors or magic will be used in the making of our product!

Idea Defined Based on Customers, Competition, Cost, Uniqueness

To design our product, we’ll first need to define it. Paradoxically, this step is both the simplest and the most difficult. It is simple because we already have a pretty good idea of what we’re going to do. We know what business we’re in (electronic security) and the kind of product we want to make.

Our customers have repeatedly told us what they’d like to see in our new DVR, and we have a rich field of competitors to mine for ideas. We know what price point we need to hit, what our capabilities are, and what it takes to put together a first-class product. So what is so difficult about defining a product?

With few exceptions, companies like ours don’t want to create “me-too” products. This means we need something of a crystal ball to predict the features our product will need when it finally hits the market, to avoid it becoming obsolete too quickly. We’ll need some “secret sauce” that makes our product stand out and gives customers a reason to select it. And we’ll want our product to be marketable for as long a period as possible; the longer it remains marketable, the more of our investment can be amortized.

Keeping our product marketable is a tremendous challenge. “Ten years ago, we saw products having 10- to 20-year lifecycles,” remarks Dave Smith, vice president of marketing for Pelco in Clovis, Calif. “Five years ago, it was around five to 10 years. With the current pace of technological innovation, today’s product designs can be expected to be obsolete in as little as two to three years.”

Other manufacturers agree, some placing the product lifetime at as little as one year. “Determining the market needs and ultimately the features required are generally the most critical and hardest to predict,” says Bret McGowan, vice president of marketing at Vicon Industries in Hauppague, N.Y. “Product development takes a long time and attempting to forecast the needs of the market at the time a product will actually be released requires a significant understanding of the trends in the market so that when it comes out, it’s not behind the curve.”

To define our idea, we’ll generate a Market Requirements Document, or MRD. This document will be a best estimate of what features the market is looking for, how much folks are willing to pay for these features and the amounto market share our company can reasonably expect if we bring such a product to market. The MRD is used to make a financial case for the product; if we’re going to spend millions of dollars to build something, by golly we’ll need to see a return on that investment.

Functions and Features Come Into Play When Defining the Product

Once the market requirements have been identified and the ROI has been examined and approved, it is time to define what the actual product will do. The Product Definition Document, or PDD, is exactly that; a written definition of what features the product will have and how it will work. This document will serve as the blueprint for our product going forward.

A PDD is usually a “living document,” frequently revised during the development lifecycle withinput from the various groups that will work on the product. It will gain more detail as we wind our way through the development process. Larger companies have mastered this part of the process, while many smaller companies see it as needless paperwork.

Ironically, a PDD is of even greater importance to a smaller company. Like any blueprint or map, following a PDD will ensure as few distractions or “side trips” as possible and avoid escalating features that consume precious time and resources. A large company can sometimes afford to get sidetracked if there are enough resources available to straighten out the course. A small company, on the other hand, once sidetracked may never recover.

As part of the PDD, engineering involvement is required. A series of negotiations are required to ensure that the features being defined are practical, can be developed in time to market the product, and fit into the product’s cost target. While many companies define this as a linear process following a logical order of steps, it is much more of a collaborative effort. The end result should be a document that defines the product and a cost in time and development resources.

Engineers Develop the Prototype That Undergoes Internal Testing

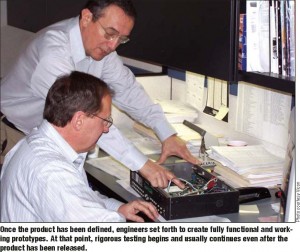

Now that a picture of our product has emerged, it’s time to start the real work. Our engineering group will develop the product, both hardware and software, until a working prototype emerges. There will inevitably be surprises, both pleasant (a new chip or component allows greater performance for lower cost) and painful (a key feature will take longer or cost more to implement).

Some companies outsource the engineering and development of portions of their product lines (see “Weighing the Build vs. Buy Proposition” sidebar above), but the steps involved remain the same.

“We are the development team behind product names that are instantly recognizable,” states Greg Stone, marketing director for DynaColor USA in Irvine Calif. “Our OEM business is based on partnering with other companies and giving them exactly what they want. We’re completely committed to the success of the products we build, regardless of the name on the box.”

The Product Definition Document (PDD) is a written definition of what features a product will have and how it will work. The PDD serves as a blueprint for the product going forward.

The end result of this engineering process will ultimately be several fully functional and working prototypes. Once these are built, the internal test process begins. The testing process seems endless, and usually continues until well after the product has been released.

“With today’s software-based products, and especially with those that work over networks, the biggest challenge is product software and network testing,” explains Smith. “There are an endless combination of environments that products can be put in and ways they can be used. Identification and elimination of software bugs prior to launch is an art.” In fact, it is inevitable that some bugs or problems will not be discovered until after a product has been installed and is working for a while.

“Water intrusion problems on outdoor domes is a good example,” says Ed Hamilton, senior program manager for American Dynamics in Boca Raton, Fla.”Wit all of the different environments and installation techniques out there, it can be quite a while before we see a problem that can be replicated in

the lab. Solving the problem is often the easy part.”

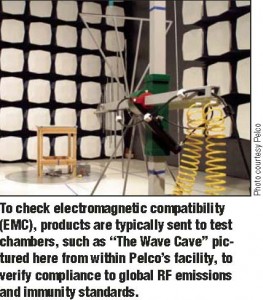

Once testing of the prototype is complete, the design is generally reviewed again for manufacturability and compliance issues. Products that will be manufactured in large quantities will often undergo a factory launch process, where pilot builds are made to set up, train and test factory readiness.

Once testing of the prototype is complete, the design is generally reviewed again for manufacturability and compliance issues. Products that will be manufactured in large quantities will often undergo a factory launch process, where pilot builds are made to set up, train and test factory readiness.

Somewhere during this phase, a production quality version of the product will be built and distributed to a limited audience for final testing. This step is known as a “beta test” in the software world, but goes by a variety of names in our industry. Tech support will usually work with the product at this point, although many companies get them involved far earlier in the process.

Some manufacturers insert a final “product validation” step. This is an internal series of tests that verifies the customer experience is what the manufacturer expects. Packaging is evaluated, and a final pass is taken to ensure the required tools and accessories are included. Manuals, and other supplemental material and documentation are double checked for accuracy.

In this way, the entire “out of box” experience is examined for improvement opportunities.

Trade Shows Are Most Popular Venue to Launch New Products

Trade Shows Are Most Popular Venue to Launch New Products

Once our product is complete, it’s time to tell the world and make it available to our customers. Most manufacturers launch major products at one of two key industry events; the ISC West show in Las Vegas in the spring or the ASIS show in the fall (this year in Orlando, Fla., Sept. 12-15).

As part of the launch event, sales and technical support people will need to be trained (see sidebar on page 59 of May issue), marketing material and data sheets should be on hand and product should be available.

In actual practice, product availability is not usually what it is cracked up to be. With two annual launch periods, the date a product must be released is often set in stone, based upon the availability of an industry event to introduce the product.

Unfortunately, all of the variables in product development can cause the actual product shipment date to slip unpredictably. The product that is displayed at the launch event is often one of the working (or semi-working) prototypes, and it is not uncommon for a product to be launched twice (or even three times) before it is actually shipped.

Support Must Be Accounted for Long After Production Ceases

Support Must Be Accounted for Long After Production Ceases

Many people don’t realize that a manufacturer’s obligation to a product does not end when the product is shipped, or even after it has been discontinued.

“We have systems out there that are more than 15 years old and are still going strong,” says Hamilton. “These must always be considered when looking at new products. Will our new dome cameras communicate with older controllers? Can we provide replacement parts for installed products once our inventory is depleted? Once you release a product, you own it for life, and that product may have a longer life than you ever thought possible.”

Not all of the steps included in this article are identified and followed in this order by all manufacturers, but most would agree with the basic sequence of events and the tasks required. Larger companies will have a team of people working on a product, each with separate and distinct duties. Smaller companies tend to combine tasks and have fewer people working on a given product. Either way, turning an idea into a finished, salable product is a complex process and a lot of work for all involved.

Most of us understand firsthand the costs associated with replacing a faulty or defective product. Repeated trips to the job site, frustrated customers, and projects that never seem to end are symptoms of products that have had a few corners cut in the development process. Although you may not be crazy about how long it takes to get a product to market, you’ll likely live with the delays if the end result is what you and your customer need.

Click Here to download this article in PDF Format